Our stories

Culture and tradition.

Please contact us to share your Traditional Teachings story.

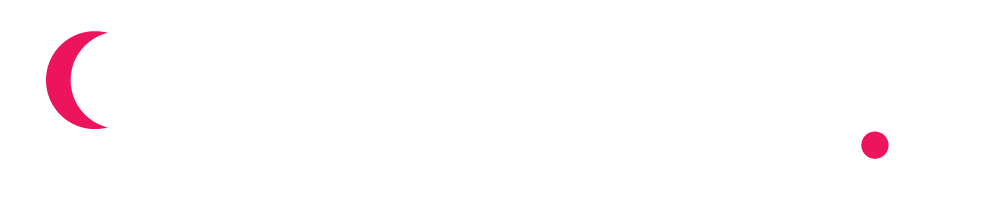

Long Line of Ladies

Long Line of Ladies is a powerful 22-minute documentary from Academy Award-winning director Rayka Zehtabchi and Shaandin Tome. It is a celebration of periods, following a Karuk community of women as they prepare for teenager Ahty’s coming-of-age ceremony, or Ihuk. The documentary captures Ahty’s strength as she learns how to conduct herself during the ceremony and what it means to embark on adulthood. It is an intimate look into the kindness and support she receives from her community rallying around her as she is taught sacred knowledge.

This film was an official selection of the Sundance Film Festival, SXSW Film Festival, American Indian Film Festival and many more. It won many awards after debuting in October 2023. Our founder Eva participated in a “Brain Trust” screening of the film earlier that summer, along with a handful of other Indigenous kwe’k (women). And she wrote a reflection about it for the Toolkit that is being used to facilitate post-screening discussions.

In May 2024 The Kwek Society hosted a virtual viewing and discussion of the film. It was terrific to watch the film with our supporters and some of the trusted adults with whom we work at our partner schools. We expected a lively discussion, and we had one! Migwetch (thanks) to all who joined us.

Read this “Short of the Week” review of Long Line of Ladies.

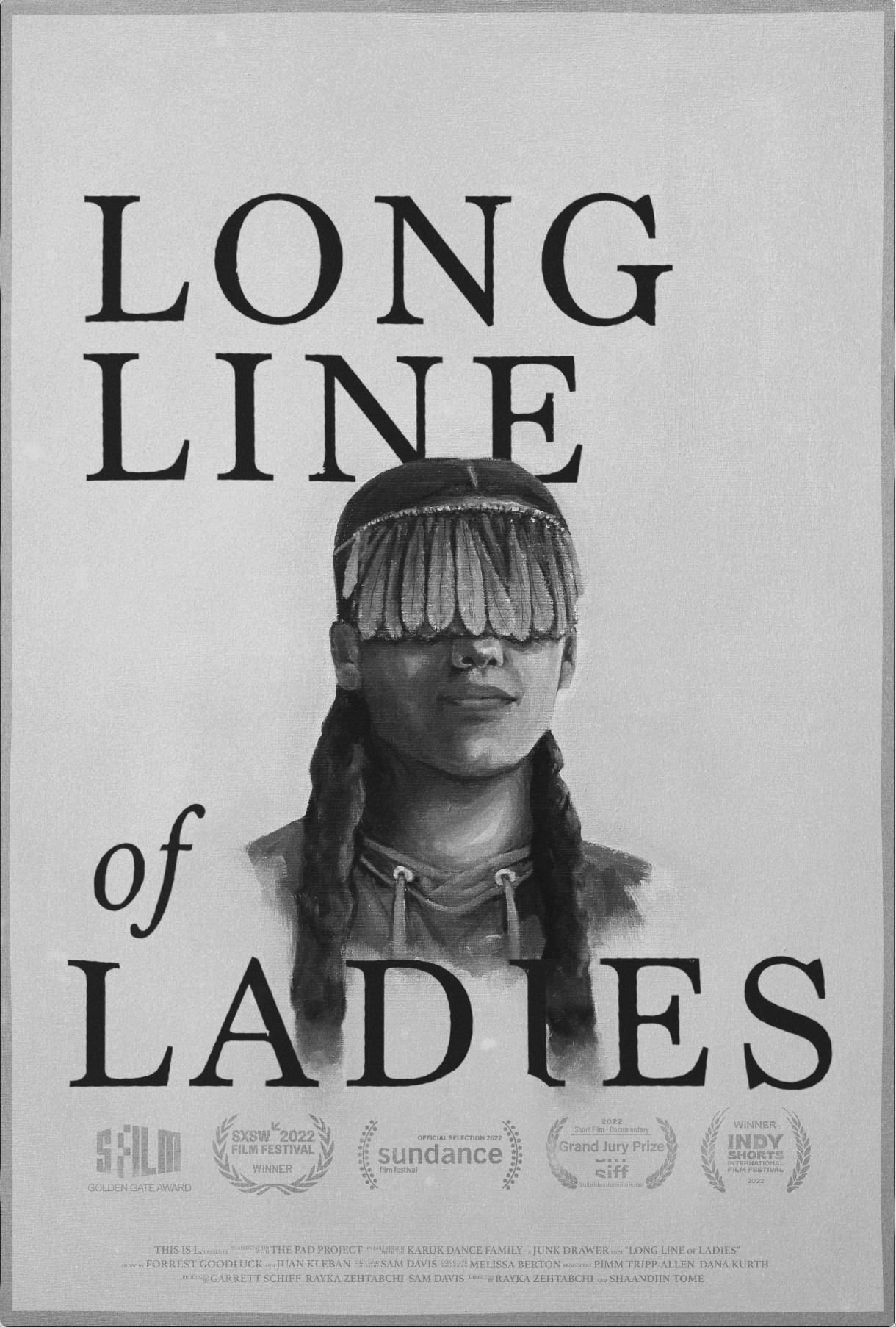

Free Period by Ali Terese

We’ve added the book Free Period by Ali Terese to the list of titles we make available to school counselors and library personnel on their request. Its publisher describes it as Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret for the next generation!

We think it would make a great holiday/winter break book for the 8 to 12 year olds in your life. We order our copies from our local independent bookstore, One More Page Books, a loyal supporter of our work to end period poverty across Turtle Island.

Hopi Teachings: The Corn Grinding Ceremony

We recently learned about the Hopi Corn Grinding Ceremony from Meet Mindy: A Native Girl from the Southwest, written by Hopi author Susan Secakuku (Mindy is Susan’s niece). It’s one of the books in the delightful National Museum of the American Indian series, “My World: Young Native Americans Today.”

Mindy shares that her ceremony lasted five days and was held at her grandmother’s house. Her aunts and grandmother were there to encourage her, but she was left alone most of the time, quietly spending the first four days using the traditional mata and matàaki, or grinding stone, to crush corn kernels into fine cornmeal. She explains how hard the work is, but how special too, since “Hopi women for many generations also performed this ceremony. … Each day, I prayed hard that I would have the strength to do well.”

Girls grinding corn in Puberty Ceremony, Shungopovi Village-2nd Mesa.

Left, Belvera Nuvamsa, Right, Mary Anna Nuvakaku, June 28, 1949 (captioned by photographer Milton Snow), available here.

As part of the ceremony, her aunts and grandmother spoke with her about what it means to be a mature young Hopi woman, the new responsibilities Mindy now has as a young adult member of her clan, and the community’s expectations of her. Mindy also describes going through a purification ceremony on the final day of the ceremony, including a ritual hair washing, noting, “Some of my hair was cut, and the rest was styled into the traditional Hopi squash-blossom hairdo, which is only worn by unmarried women.”

After the ceremony concluded, “I walked through my village,” Mindy says. “The people who saw me wished me well, and the men said a special prayer for me to live a long and healthy life and to have a good marriage and strong children. When I got to my mother’s house, she was there to greet me with my grandmother and aunts. Then, the men in my family joined us for a feast.”

While she isn’t ready to get married quite yet, Mindy believes it was important for her to participate in the ceremony. “The ability to give life is sacred, and as we get older and develop that power and responsibility, it is important to spend some time thinking about this. … Now I’m a young woman in Hopi society, and I’m expected to help more, to be more responsible, and to continue to learn more about Hopi traditions and my clan.”

We encourage you to buy Meet Mindy: A Native Girl from the Southwest or borrow it from your local library to read more about modern Hopi life, Hopi history and traditions, and to see the lovely photos Mindy shares from her Corn Grinding Ceremony.

Introduction to Berry Fast Teachings

Introduction to Berry Fast Teachings

In Anishnabe Territory, there is an important fast for young women — the Berry Fast. Shkini-kwe (process of giving life) is a year-long fast that begins when young women start their menstrual cycle and ends with a coming out ceremony.

During that year, life slows down. Young women spend this special time with aunties, grandmas and female role models to learn about womanhood and the giving of life while hearing stories such as the tradition of the Berry Fast. They are encouraged to be with themselves and reflect. They also collect berries during harvesting season, saving them for their coming out ceremony to share with others as a reminder that we are to always think of those around us.

Shared by: Winona Elliott is Potawatomi and Ojibway from Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation located on the Bruce Peninsula in Ontario, Canada. She belongs to the Moose Clan from her father’s side, and also acknowledges her mother’s clan, the Fish Clan.

Sharing Berry Fast Teachings

Sharing Berry Fast Teachings

In Anishinaabe culture, more specifically in the Ojibwe, Bodewadmi, and Odawa Nations, the rite of passage ceremony from girl to womanhood is known as the Berry Fast or Strawberry Fast. While the ceremony can vary from region to region, there are some shared fundamentals. At the time menstruation begins, girls begin a fast and refrain from eating for a period of a few days. They also begin a year-long fast in which they refrain from eating berries of any kind. During that one-year fast, girls receive the teachings of water, life-giving, and womanhood from the women in their families and communities.

The berry fast is a time of celebration. Communities offer many different supports to the girl, including providing crafts and supplies for skill building and craft making so that the girl learns how to use her hands and work hard, and receiving teachings on personal hygiene, self-respect and personal space, healthy relationships, healthy sexuality, and ways to support other women, Elders, and community members. Over the year, the girl learns to understand her strength, the sacredness of her monthly menstrual cycle, and the power she has as a water-keeper and life-giver.

When the year-long fast ends, a coming-out ceremony takes place to reintroduce the new menstruator to the community as a young woman. The ceremony breaks the young woman’s year-long berry fast with a community feast that includes berries and a giveaway that features gifts the young woman learned to make during her year-long fast.

Assisting with a Berry Fast Ceremony

With many living in urban centers or away from their grandmothers or other elders who may hold the berry fast teachings, there are ways we can still support women to begin and complete their berry fast. Here are quick and helpful tips to help assist young women in your life who may be contemplating a berry fast ceremony.

- Talk to them about becoming a woman. Let them know all that is part of the process of becoming a woman. Discuss the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual changes. The more we talk to them about becoming a woman when girls are young, the less surprised and shocked they will be and the more open and excited they will be about the changes they will experience.

- Learn about the berry fast teachings and share what you know. You don’t have to be an expert; sharing any knowledge you have is important. Share about how incredibly special it is to be an Indigenous woman and about the roles and responsibilities of women as life-givers, waterkeepers, and protectors, and talk about the cycle of women’s lives. The more we talk about these things, the more familiar they will become for girls especially if they live away from the community and/or culture.

- Practice fasting to prepare girls for the one-year berry fast. Spend a weekend fasting with your girls by camping or isolating them away from the family. Share stories of womanhood, sing songs, craft together, and teach hands-on skills while refraining from eating or drinking as you prepare them for the berry fast. (If you need to drink water, please do so; it is important to convey that doing one’s best is what’s important.) Remind them that the practices you are sharing are those the ancestors lived throughout our history and that there are teachings behind each step of the berry fast.

- Adapt the berry fast to your environment. When girls begin their moon cycle for the first time, guide them to begin their berry fast wherever they are — in their rooms at home or in a tent in their backyards. If there isn’t a grandmother, elder, or knowledge-holder nearby with berry fast teachings to share, that is okay. Over the course of 365 days, you can aim to have them fast in isolation for a total of ten days. You might split these into five days at the start of the first moon cycle and five days at the end of the year; choose whatever works best for the faster’s schedule. During their isolation, they will not eat or drink, and they will not take in any media of any sort or interact with any men. Help them learn hands-on skills like crafting, beading, sewing, and making gifts by hand. If you have friends who are willing to share, have them visit to share skills that they have and to share their stories about becoming women. At the start of the first fast, call your circle of women and girlfriends to share the news and celebrate with them that a berry fast is starting! Provide the berry faster with the rules governing the berry fast year, as you understand them, and ask your circle of women and girlfriends to provide support as she works to follow the teachings of the berry fast ceremony. Then call all the supporters together at the end of the year to celebrate her with a giveaway and feast at which you introduce her to all as a new young woman in your community/circle.

While it is encouraged to start a berry fast ceremony at the beginning of the first moon cycle, it is entirely possible for a woman to have a berry fast ceremony at any time in her life.

Ch’iwa:l — Hupa coming-of-age ceremony (Flower Dance)

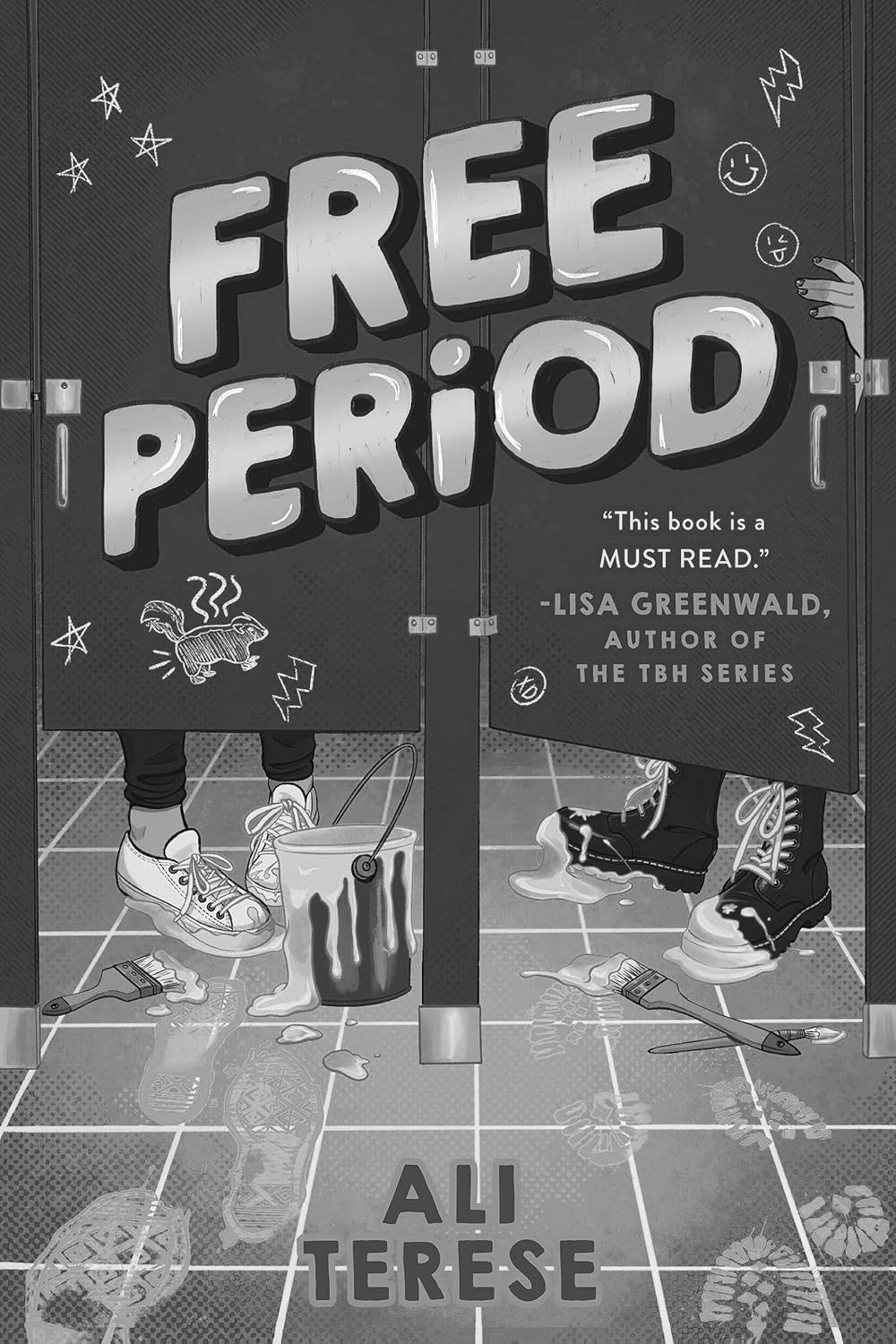

Cutcha Risling Baldy’s book, We Are Dancing for You, explores the cultural revitalization of women’s coming-of-age ceremonies. She notes that these ceremonies demonstrate how women are foundational to their individual communities and how women’s experiences are central to nation-building, culture and spirituality.

The book includes an account of the Hupa tribal community’s coming-of-age ceremony, Ch’iwa:l, which lasts for three, five, or 10 days and is held after a girl starts menstruating. The ceremony is a public celebration that includes specific practices and ritual guidelines for the new menstruators, called kinahłdung (Flower Dance girls). Running is a significant part of the three-to-10-day ritual activities, as it is believed that how the young woman runs demonstrates how she will live her life. During the day, visiting women who offer advice attend to the young woman; older women teach songs, prayers, and skills. The young menstruator ceremonially bathes in the river and steams with herbs each day. As she picks herbs for her steam bath, she must grind them in a deliberate way.

Dr. Risling Baldy writes: This kind of meaning and metaphorical representation can be found throughout the ceremonial practices, and the Hupa value their community and public aspects. There is no shame in the celebration of a first menstruation and bringing the community together illustrates to the girl (and the community) how important these young women are to the tribe and culture.

Further discussion of the ceremony and of its revitalization can be found here. We celebrate Dr. Risling Baldy’s statement:

We are not sad, dying Indians and this documentation of our revitalizations is not of a dying culture, but instead of a culture that has always envisioned an Indigenous future. In Hupa when we end a story we say hayah-no:nt’ik’, which means “that’s the end of it” or “the story extends to there.” But it has an additional meaning, “it reaches so far,” as if to remind us how our stories stretch into our future and that we are always reaching forward.

Photo by Trish Oakes, courtesy of Melitta Jackson and Marlette Grant-Jackson

Personal account: The Flower Dance Ceremony

Katie Jäger-Bowie, a Citizen Potawatomi Nation tribal member living in Northern California and a Kwek Society supporter, recently shared with us her personal account of the Flower Dance coming-of-age ceremony Katie and her family and community celebrated with and for Katie’s 18-year-old daughter, Trinity. The ceremony is a tradition that has been revived by the Yurok, Hoopa Valley, and Wiyot tribes, heritage Trinity shares with her father.

Katie told us that Trinity’s ceremony took place over a few days, during which Trinity ran across culturally significant tribal lands, wore varied regalia that Katie made for her, and participated in an evening of community song and dance that welcomed Trinity into her role as a woman and an adult. During this evening ceremony, Trinity wore a blindfold as those around her danced and sang in rounds from sundown until sunrise. Trinity was instructed to remove her blindfold as the morning ceremony began and then was presented as an adult to everyone present. All then enjoyed a community feast with bowls full of berries and other delicious foods.

Katie also shared with us that, in preparation for her Flower Dance ceremony, Trinity completed a ten-day traditional acorn fast. Around the same time frame, Trinity also completed a ten-day berry fast in acknowledgment of her Potawatomi heritage.

Katie told us that she encouraged Trinity’s participation in the ceremony because others in the community who have had a Flower Dance ceremony “talk about how important it was to them later in life.” Katie noted that they “reflect back on that time,” and understand that the endurance and discipline they demonstrated in preparing for and participating in the ceremony taught them that they could accomplish whatever they set their minds to, that they could do anything.

Chi migwetch (big thanks), Katie and Trinity, for this first-hand account of Trinity’s Flower Dance Ceremony. We love sharing traditional teachings about menstruation because, as Katie put it, “Getting your moon makes you sacred; it is not something to be ashamed of. When you become a woman you have life-giving power inside of you.”

Isnati Tipi Ceremony

The Isnati Tipi ceremony was brought back in Eagle Butte, South Dakota, over a decade ago. The daughter of one of The Kwek Society’s key supporters was in the first group of girls who participated. The details we are sharing here come from this supporter and from published reports of the ceremony. You can hear and read a short piece on the ceremony, posted by the Kitchen Sisters in 2015, here.

The four-day ceremony begins with the participants each putting up their own lodge, or tipi – demonstrating the strength to house themselves – and with the other participants, forming a “moon camp.” Traditionally, the tipis have 13 poles because women have 13 moons in a year. The camp is called a “moon camp” because it provides a special time for young women to learn about their bodies and much more. The young women are supported by their older female relatives, who feed them and care for their personal needs. The young women gather traditional herbs and medicines near the camp and are instructed on their uses. They also gather chokecherries or buffalo berries for the creation of wasna, a traditional food made of ground-dried meat, fat, and crushed berries, and learn ceremonial songs and beading.

Throughout the days, the older relatives talk with the young women about their new roles as women and their new place in their families, communities, and tribes. Topics are far-ranging: self-respect, healthy relationships, nutrition, and sexual and mental health are among what’s discussed.

Taking part in the ceremony establishes a sense of self and identity. At the close of the four days, the participants are introduced to the community as women and receive their adult names.

Our wise supporter explained the ceremony’s renewed purpose: “When you know what your responsibilities and expectations are, your role in society – which has nothing to do with mainstream society and the warped perception of women’s and even men’s roles — is solidified. As Native people, our places were taken from us. We are slowly taking them back. Through this ceremony and other work, we not only are strengthening our young women, we are strengthening our communities and tribes.”

First Nations Women’s Teachings

First Nations Women’s Teachings

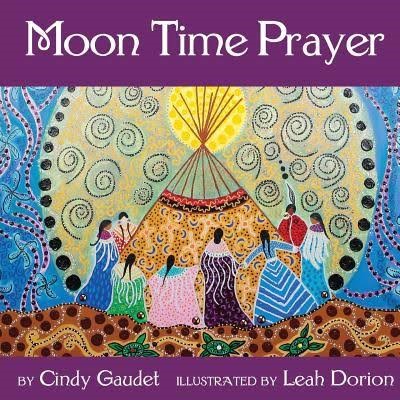

We heartily recommend Moon Time Prayer in its entirety.

We have long admired this lovely book. As noted in the book’s foreword, written by Grandmother Isabelle Meawasige: “These women’s teachings touch upon the power of the Moon, the Earth and their connection to women… In the beginning times, the teachings appeared in spoken stories, known as tales of power.” We are honored to have the permissions to quote from this book and to share with you the cover illustration. Migwetch (thank you) to author Dr. Cindy Gaudet, illustrator Leah Dorion and publisher Mother Butterfly Books. Here are some excerpts from this special book:

In Indigenous culture, the Moon is known as Grandmother Moon and is connected to women’s sacredness, as well as to the roles and responsibilities that come with being a woman. The Moon is the weaver of the tides and the leader of the waters of the Earth. Grandmother Moon also governs the waters inside women. One of these watery experiences is known as Moon Time, or the menstrual cycle.

Grandmother Moon governs all life cycles from birth to death through her powerful magnetic pull. Her work is to weave magic into the heart of all of earth’s creations.

Once every twenty-eight days, the fullness of the Grandmother Moon illuminates the night sky. This also is when the spirt of the moon dances within woman. Every twenty-eight days, her vibrant red blood Fows to nourish the earth mother.

As women we are connected to Grandmother Moon and She hears us. Our Moon Time cycle is linked with her. It is through Her that we receive our strength to go inward. And it is with the assistance of Grandmother Moon that all life pushes forth. The plants, the trees, and babies.

Remembering the sacredness of our Moon Time and our womanhood is how we create harmony in our own heart, in our family and in our entire community.

Apache Sunrise Ceremony

Apache Sunrise Ceremony

After their first menstruation, Apache girls, with their families’ extensive planning and support, may choose to participate in a traditional and sacred puberty rite ceremony. During that time, girls strengthen their bodies and minds and embrace their role as Apache women.

The Mescalero Apache Tribe describes the Sunrise Ceremony as “a four-day ‘Rite of Passage,’ a ceremony that marks the transition of an individual from one stage of life to another, from girlhood to womanhood. A young girl celebrates her rite of passage with family-prepared feasts, dancing, blessings and rituals established hundreds of years ago. It emphasizes her upbringing which includes learning her tribal language and instilling, from infancy, a sense of discipline and good manners.” Read more here.

Kiana’s Apache Ceremony, a 2020 film that documents a White Mountain Apache ceremony, and the 2017 video, Inside an Apache Rite of Passage into Womanhood (2017), capture the ceremony’s traditions and meaning. Developmental psychologist Carol A. Markstrom offers an in-depth discussion and analysis of the ceremony as practiced by various Apache communities in her book, Empowerment of North American Indian Girls: Ritual Expressions at Puberty (Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2008).

Diné (Navajo) Kinaaldá Ceremony

Diné (Navajo) Kinaaldá Ceremony

During our work with Diné (Navajo) students and community members, women have shared with us certain aspects of the traditional Kinaaldá ceremony, which takes place in the days following a young woman’s first period. This Blessing Way ceremony typically lasts four days. In that time, a young woman on her first period is joined by her family and community members in singing, praying, and telling stories to help shape her. She’s expected to run multiple times each day and to work for her community – grinding corn and baking a very large corn cake, called an alkaan, by burying it in an earthen pit and setting a fire on top to bake the cake. On the last night of the Blessing Way ceremony, a medicine man or woman is called to help lead prayer and songs and other aspects of the ceremony, and prayers are sung through the night. As the sun rises, the young woman runs one last time toward the sun until the final songs of the Blessing Way ceremony conclude. The final rituals include sharing the corn cake and sweets with everyone assembled. You can hear parts of the traditional Kinaaldá, songs and rituals here.